Tools for Decoding Cross-cultural Communication: Mazhar and Islam as a Blanket

By Gabriela Phillips

I must admit that the first time Mazhar Mallouhi told me, “Here is something that most people in the West may not understand: Islam is the blanket with which my mother wrapped me when she nursed me...” I was not sure I was getting it myself.

I had been aware of the huge gap between his Arab Bedouin, Islamically-shaped mental map and my Argentinean, European-shaped, Christian one. So, almost instinctively I said, “How lovely, I can feel your mother’s love”, a rather superficial and unengaged response. At least I could connect at the sensorial level and sense the warmth and emotional attachment with his mother and with Islam. But Mazhar had prefaced his comment with clarity: “…most people in the West may not understand.” He was speaking about ideas, not feelings.

Yes, there is a gap between our worlds: different assumptions, different categories; different values, and beliefs that are the building blocks for our mismatched mental maps. Maps that we inherit and seldom question. And maps are key for navigating and making sense of reality. Thus, when I say home and Mazhar says home, we share similar physiological brain functions but have different ways of thinking about the home. We connect different ideas to home, and translate those ideas into different practices and behaviors. If I visit his home, he will greet me with “ahlan wa sahlan” which means “you are with your people now (not an outsider), and you are not a burden”. Do you know why we say “welcome”? Go ahead, now do your research!

Much of the cross-cultural misunderstanding comes from not looking underneath the hood and applying our meanings to the Mazhars around us.

Mazhar is a gracious follower of Jesus trying to help me understand his complex identity as an Arab Syrian, with Bedouin roots who is a follower of the Messiah. So, I followed my initial irrelevant comment with a question, “Brother, what are we missing as Western Christians?” Of course, a “straight” answer would have been preferable, but instead, he added in traditional poetic style, “Our Islam was embedded in my mother's milk and in her prayers. I inherited Islam from my parents. It was the cradle that held me until Christ found me.”

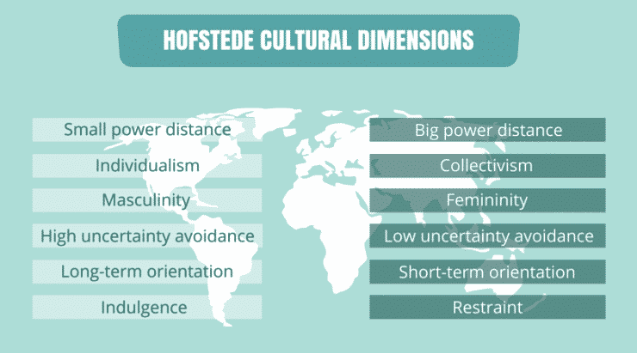

How do you unpack a conversation like this? Hofstede’s cultural dimensions can help. What is Mazhar’ saying about power distance? Is his identity individualistic or collectivistic? What about gender roles? What about avoiding risk taking? So applying these lenses, this is what I saw.

Mazhar’s Islam is not his personal religion which he can change as soon as he is old enough to decide. In his tribal (collectivistic) context, survival depends on journeying up close together because the lone ranger doesn’t make it alive out of the desert. It’s a matter of life and death, not personal fulfillment. And in this desert, Islam is that guiding force, the ancestral clan leader during the day and the shared blanket under which every child finds protection from the cold of the night. Islam is the tent that gathers who is in and marks the boundaries of who is out. Read “out” as the dangerous and deviant “outsider” (new ideas, western Christianity) that is not part of us.

This Islam came from Mazhar’s mother's inner being, her very own breasts. It is the nurturing milk provided by the Creator that mixed with prayers and became the source of life. It is not strange that Mazhar spoke of his mother and not his father; after all, didn’t Mohammad say, “Paradise lies at a mother’s feet?”

“What about Jesus, Mazhar, what is his rightful place?” I asked, and without hesitation he said, “Islam is my heritage, Jesus is my inheritance. He is my Lord and my Shepherd that leads me home.” And then, as if reading my next question, he added, “You as a Christian need to know this: Islam is my mother. And you will never get my respect by telling me that my mother is ugly, no matter what she may look like.”

In Mazhar’s world, the wiser you are the less you speak. And his words: “Islam is my heritage, and Jesus is my inheritance” made me ask, “Who is Jesus to me? To us? Who is ‘us’ anyway?”

Dear Pastor, if you are going to gain deep insights into how God works in a different community, and/or to communicate Good News that others can hear, start by listening with curiosity. Listening is key for cultivating a deep cultural self-awareness and understanding (i.e., how one’s beliefs, values, perceptions, interpretations, judgments, and behaviors are influenced by where one belongs) and how to enter into someone else’s community and communicate something of value to them.

Gabriela Phillips serves as the coordinator for Adventist Muslim Relations in the North American Division.