Power Distance: Neither Distance nor Powerlessness

By Gabriela Phillips

The most glaring image under the caption “power distance” comes from a meeting we had with a high official in Azerbaijan. We were sitting across this enormous table, having to literally shout to hear each other; and in between us, half a dozen of the old fashioned dial-up phones served to mark the status between him and us. This was in the 90’s right after the fall of the Soviet Union. The room was spatially organized to communicate clearly who called the shots, and the “appropriate” roles between “patrons” and “clients.” In other words, the distance between leaders and followers: power distance.

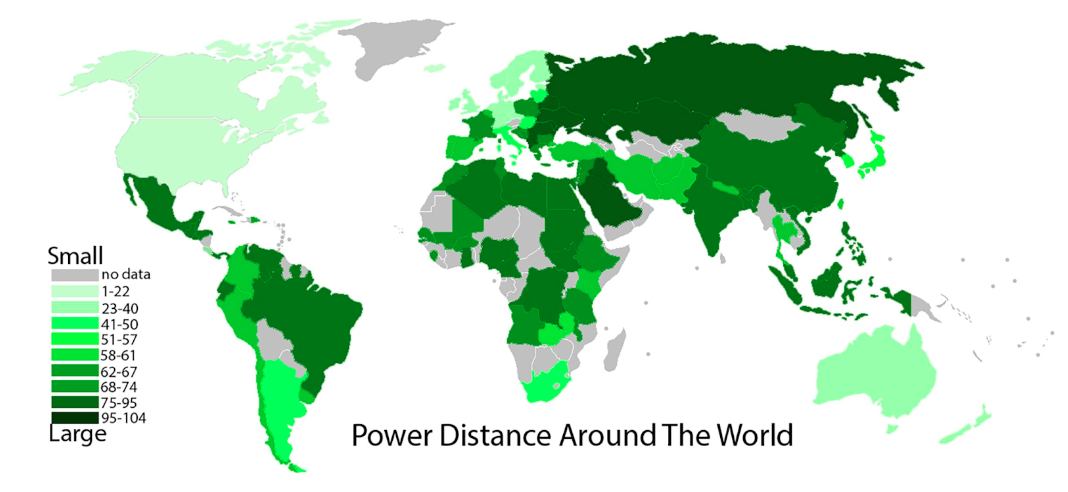

Anthropologist Geert Hofstede coined the phrase "power distance" to describe the ways that some cultures prefer the powerful to look and act. In high power distance cultures, power is made visible and tangible, and dramatic differences in power are seen as a natural, indeed crucial, part of a healthy society. This is not about proper respect or deference, which is a sign of dignity and good manners and acceptable protocol, but about decision-making power and how we view the intrinsic value of each other.

In low power distance cultures, on the other hand, visible hierarchy and signs of power are discouraged. Those with power are expected to treat others as equals, not as subordinates.

https://geerthofstede.com/culture-geert-hofstede-gert-jan-hofstede/6d-model-of-national-culture/

Years ago we visited India, where power distance is the greatest, with a Californian friend whose view of power is very flat. That evening, a group of Indian sisters bowed down to touch her feet as a sign of respect for my friend as an elder. It was something new for my friend, so she lifted the women up, shocked and displeased and gave them a warm hug and a kiss on their cheeks. I could sense the immediate disconnect between them because they did not share a common understanding of status. The Indian women were showing respect and desired to be blessed with the knowledge of someone older. My Californian sister wanted to communicate that in Christ we have equal value.

In every culture there is an invisible matrix that dictates how power is to be distributed. In the parable of Jesus, the head of the household had a sort of mental metric that helped him to categorize the value of his guests, the manifestation of which was the seating arrangement at the table: “No friend, not you at the head… I have to demote you… sorry for the embarrassment but it’s your fault for assigning yourself a higher value (honor) than I do” (based on Luke 14:7-11).

The culture in which Jesus lived embraced a patron-client cultural construct which supports an unequal power distribution amongst members of society. However, Jesus empathetically stated that the disciples were not to rule from the patron-client model but rather those in the highest positions must become like those in the lowest positions. Jesus instructs his disciples not to lead as the culture dictates, so he washed their feet, even though he was the Master. “Do you know what I have done to you?" Jesus asks. "You call me Teacher and Lord—and you are right, for that is what I am" (John 13:12–13, ). But Jesus did not deny that there was a difference between him as a Master and those who were not. The point was, “Yes I am, but I chose to use my power as a Master not to lord it over others, but to love as reflected in acts of service, for I am humble.”

So, how can we cross this bridge?

Recognize that power is not something dangerous to be avoided but a gift to be stewarded and which Satan has appropriated.

Power is not the opposite of servanthood. Rather, servanthood is the very purpose of power. The higher you are, the more opportunities you have to serve and bless.

Every culture has a value system which needs to be assessed not in relation to my culture, but in comparison with the Kingdom values we receive from the Bible. Power is not given to benefit those who hold it but for the building of the body of Christ.

Do not avoid conversations about power; power distance exists and it helps to bring out biblical examples of how Jesus dealt with and re-interpreted it.

Present the cross as a manifestation of power that challenges pride and love for status.

Using the tools of cultural intelligence, here are three potentially different responses my friend could have had:

1) “Sisters, I am not familiar with what you did. Can you explain why this is important to you?”

2) “I see, you wish to get wisdom and a blessing. I want to pray over you the prayer of Aaron, ‘The Lord bless you and keep you; the Lord make his face shine on you and be gracious to you; the Lord turn his face toward you and give you peace.’ Numbers 6:24-26”

3) “I encourage you to pass this blessing on to others, because this is pleasing to God.”

Gabriela Phillips serves as the coordinator for Adventist Muslim Relations in the North American Division.