Bad Bunny, Diaspora, and the Primacy of Christ

The healing the diaspora longs for finds its completion not in a cultural moment but in the person of Jesus.

Published in Heute under an Attribution 4.0 International license.

A Table Full of Sides

When I was in my twenties, I felt like I had been deprived. It felt like I was raised deprived of Puerto Rican or Dominican culture. For food, my parents raised us vegetarian, so every dish was a side—no mains. For culture, we sang from the Spanish-language hymnal for family worship and read from the Bible in Spanish. There was no popular music, and we didn’t eat meat. I learned Spanish in worship, and my cultural exposure in the diaspora was limited to church communities, even when visiting Quisqueya or Borinquén. The diaspora experience has a way of producing this hunger—a longing for something you feel you should have inherited but didn’t quite receive in full. You grow up surrounded by the culture’s warmth but not always its substance, hearing the music but not always knowing the lyrics, present at the table but eating a translated version of the meal. Everything felt like a side dish. I wanted a main course.

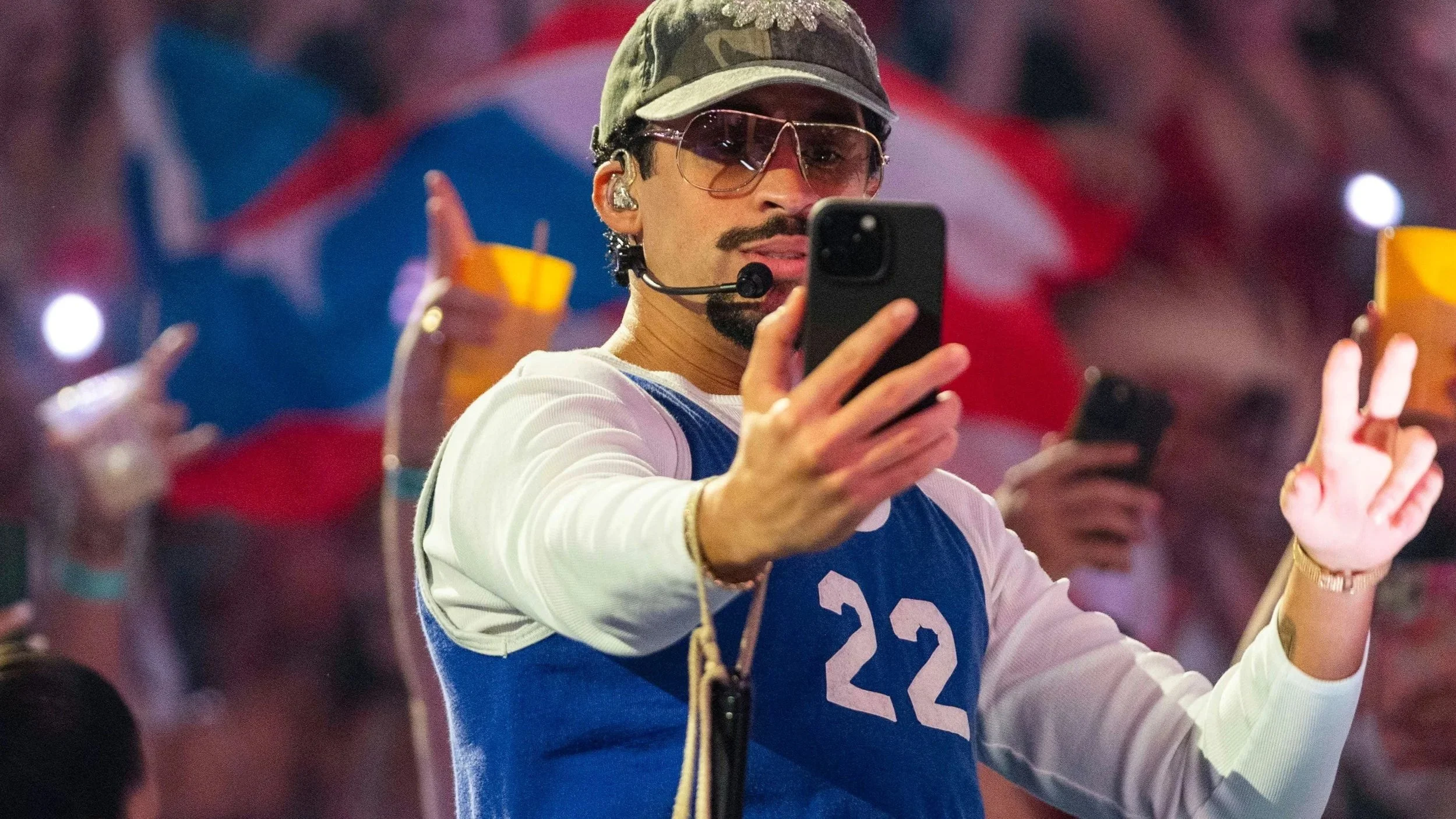

The Appeal of Being Seen

I can see the appeal of cultural figures like Bad Bunny. When the nation’s top politician diminishes as other (and not us, or ours) a Puerto Rican artist, there is a strong temptation to embrace Bad Bunny as a banner bearer for the whole diaspora. Bad Bunny makes visible to the United States the culture, sounds, and movements of an island of proud, incredible people. For millions of Puerto Ricans scattered across the mainland, living between two languages, two kitchens, two calendars of holidays, he functions as a cultural ambassador, someone who refuses to code-switch or apologize for who he is. That refusal resonates. In a political climate where Latino identity is flattened, mocked, or weaponized, Bad Bunny’s unapologetic pride feels like oxygen. And for those of us in the diaspora, where identity is always being negotiated, it is easy to see why his music becomes more than entertainment; it becomes a declaration of existence.

The Filtered Inheritance

H. Richard Niebuhr, in Christ and Culture, describes the enduring tension between the claims of Christ and the claims of the surrounding culture—a tension that never fully resolves on this side of eternity. For the child of the diaspora raised in a devout home, that tension is compounded: it is not merely Christ against the dominant culture, but Christ as the filter through which your parents interpreted their own culture before passing it on. My parents did not deprive me of my heritage; they gave me their heritage as they understood it: through the lens of faith. The hymnal was not a substitute for the culture; it was the culture, refracted through what they believed mattered most. I did not see it that way at twenty. I see it more clearly now.

Niebuhr offered several postures the church has historically adopted toward culture: Christ against culture, the Christ of culture, Christ above culture, Christ and culture in paradox, and Christ transforming culture. Each has its temptations. The “Christ against culture” posture risks making faith an escape from identity, a sterilized existence stripped of sazón and sabor. The “Christ of culture” posture risks the opposite: baptizing everything in the culture uncritically, as though the flag and the cross are interchangeable banners. For the diasporic Christian, the most honest posture may be a transformational one: Christ does not abolish culture, but He insists on primacy within it. I can love the sound of the cuatro, weep at the story of la Masacre de Ponce, cook habichuelas guisadas even in its vegetarian form, and still say: None of these things are ultimate. Christ is.

The Answer Culture Offers

I want to say today that I don’t feel deprived. I don’t feel that my sense of pride in having a Puerto Rican father is diminished by my rejection of Bad Bunny as a cultural figurehead for myself or for others. For the Christian, it is a poor exchange—not a poor rejection—to trade the primacy of Christ for the primacy of cultural representation, however powerful that representation may feel. Bad Bunny himself has said that the answer is love. And that is an attractive offer. Culture always makes attractive offers. It tells the diaspora child: here is where you belong; here is what will make you whole; here is the love that will heal the fracture of living between two worlds. But Christianity does not give us love as the answer—not love as the world defines it, untethered and self-referencing. Christianity gives us Christ. And in Christ, love is not an abstraction or a sentiment; it is a Person who suffered, died, and rose so that fractured people from every nation and tongue could find not merely belonging but wholeness. The healing the diaspora longs for, the mending of what was lost in the crossing, the restoration of what colonialism stole, the dignity that politics denies is real and legitimate. But that healing finds its completion not in a cultural moment but in the person of Jesus, in whom all things hold together.

The Host, of Course! A Potluck, Not a Main Course

I began with side dishes, with the feeling that my upbringing gave me a table full of sides and no main course. I have come to see that metaphor differently. The kingdom of God has always looked more like a potluck than a prix fixe. At a potluck, everyone brings what they have. The Puerto Rican brings the arroz con gandules. The Dominican brings the mangú. The Jamaican brings the rice and peas. The Korean brings the kimchi. And none of these dishes compete with one another, because none of them is the main course. Christ is the main course. He is the center of the table around which every culture gathers, and it is His presence that turns a collection of sides into a feast. My sons and I saw this lived out as we viewed the Super Bowl at our church, Danbury Bethel SDA, sharing food with friends. We did have a potluck; the stream was turned off during the half-time show.

This is where the celebration of diversity finds its true footing—not in the modern insistence that our cultures or nations are our identity, but in the gospel’s declaration that our identity is in Christ, and our cultures are the offerings we lay before Him. When the primacy is right, the diversity becomes beautiful rather than competitive, generous rather than defensive. I do not need Bad Bunny to tell me I am Puerto Rican. I do not need a politician’s approval to know my heritage has dignity. I know who I am because I know whose I am. And at His table, there are no side dishes—only a feast of nations, gathered around the Lamb, each contributing something irreplaceable, and none mistaking their contribution for the Host. And to echo Daddy Yankee, who rejected an invitation to participate in Benito's show, the best touchdown Benito will make is when he gives his heart to Jesus. ¡Que Dios los bendiga!

Johnny Ramirez (LLU M.S. Chaplaincy, ‘26) is an NAD ACM endorsed chaplain working full-time in hospice. He is married to Rachelle (née Wareham) and they are parents of George and Andrew. Together they live in Wilton, CT.